Intersections of Climate Psychology, Personal, Bicultural and Pastoral Practice

This seems to be work I am given to do: to articulate the pastoral challenges of climate change. By which I mean the impact on people and church of a warming world. How do our spirits, hearts and minds respond to evidence of climate change? What are the flow-on effects for faith communities? How do we care well for each other, in the name of Christ? I want to start at the beginning, look beneath the surface, and point towards practical implications for pastoral ministry.

I am learning to be a good Treaty partner, and my internal map for that journey sets the starting point a long way back, before now.[1] Back to my ancestors in England who responded to changes in the world they knew by packing up the kids and what little they had into a boat and building a new society on the other side of the planet. They passionately knew that God journeyed with them and that God met them here in New Zealand. My family was blessed: by God, by bonds of love, and by the systems of colonisation. My children carry forward that double blessing of white privilege and a strong sense of wellbeing and identity. Their generation will need all the blessing they can draw on as they face a warming world.

My work begins with faith and is founded on living relationship with Jesus. I value my ordination and my counselling training. I seek to resource the church and the wider community sector for responding effectively to climate change. There are various paths I walk. The topic of this article is pastoral practice, which is an intersection, one of those places where tracks meet and signs point in various directions. In this article I identify three of these paths: climate psychology, self-awareness and pastoral care. These are vital contemporary steps in long story of faithful service in challenging times. And walking through this reflection is the question of what it means to honour the Treaty of Waitangi as Pākehā.

Why climate change? Is it really that big a deal? How you enter this conversation depends on how seriously you take the threat of the climate changing. We have come through crises before – yes, that’s true. This is big, global, and pervasive – also true. Environmental destruction and pollution impacts every place on Earth and every community – definitely, but we are in a time-lag; we know it’s happening but we don’t know what the impacts will be. We hear warnings and prophecies but we don’t know if these exaggerate or minimise the threats. We look around us, unsure whether to ignore or freak out. Neither option seems adequate.

As a teenager I loved Douglas Adams’s book; he describes the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy as having “DON’T PANIC” printed on the cover in large friendly letters. When I look at the church this is what I see. Reassuring calm is an awesome thing to offer but it is not enough. I wonder if the church is afraid of fear itself, let alone anger, despair or conflict. My invitation is to face all the feelings, including the ones we don’t like. Climate psychology tells us what other people are feeling about climate change. Self-awareness tells me how I feel about it. Pastoral care is how we listen in ways that encourage faith, healing and courage.

I am learning to be a good Treaty partner, and my internal map for that journey sets the starting point a long way back, before now.[1] Back to my ancestors in England who responded to changes in the world they knew by packing up the kids and what little they had into a boat and building a new society on the other side of the planet. They passionately knew that God journeyed with them and that God met them here in New Zealand. My family was blessed: by God, by bonds of love, and by the systems of colonisation. My children carry forward that double blessing of white privilege and a strong sense of wellbeing and identity. Their generation will need all the blessing they can draw on as they face a warming world.

My work begins with faith and is founded on living relationship with Jesus. I value my ordination and my counselling training. I seek to resource the church and the wider community sector for responding effectively to climate change. There are various paths I walk. The topic of this article is pastoral practice, which is an intersection, one of those places where tracks meet and signs point in various directions. In this article I identify three of these paths: climate psychology, self-awareness and pastoral care. These are vital contemporary steps in long story of faithful service in challenging times. And walking through this reflection is the question of what it means to honour the Treaty of Waitangi as Pākehā.

Why climate change? Is it really that big a deal? How you enter this conversation depends on how seriously you take the threat of the climate changing. We have come through crises before – yes, that’s true. This is big, global, and pervasive – also true. Environmental destruction and pollution impacts every place on Earth and every community – definitely, but we are in a time-lag; we know it’s happening but we don’t know what the impacts will be. We hear warnings and prophecies but we don’t know if these exaggerate or minimise the threats. We look around us, unsure whether to ignore or freak out. Neither option seems adequate.

As a teenager I loved Douglas Adams’s book; he describes the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy as having “DON’T PANIC” printed on the cover in large friendly letters. When I look at the church this is what I see. Reassuring calm is an awesome thing to offer but it is not enough. I wonder if the church is afraid of fear itself, let alone anger, despair or conflict. My invitation is to face all the feelings, including the ones we don’t like. Climate psychology tells us what other people are feeling about climate change. Self-awareness tells me how I feel about it. Pastoral care is how we listen in ways that encourage faith, healing and courage.

1: Climate Psychology

There have long been disciplines within psychology which explore how people relate with their environment. Over the past decade ‘climate psychology’ has emerged with a distinctive voice, naming mental health impacts of climate change and concluding that “emotions shape people’s reactions to the climate crisis in profound but complex ways.”[2] Researchers explore emotional responses including anxiety, grief and anger and the cognitive defences that enable people to ignore or deny bad news. Panu Pihkala notes the differences between ‘emotions’ as conscious feelings and ‘affect’ which is a body experience, as well as ‘mental states’ such as numbness or overwhelm, and ‘moral’ emotions such as concern for victims of a disaster in another country.[3]

Is feeling bad about climate change a bad thing? To pathologise or not to pathologise? The powerful American Psychological Association decided not to define climate anxiety as a form of mental illness, moving away from an individualist medical model to call attention to “justice, equity, and mental health considerations.” “While resilience efforts are necessary to protect the physical and mental health of people and communities in the face of climate change, they fall short of addressing the problem at its root. Rapid transitions … require multilevel governance, policy instruments, institutional capacity, and investment.”[4] Christina Johannessen argues that “climate change stress should not be seen just as a problem to be solved or a condition to be medicated but rather an important encounter with our awareness of our impact on the world.”[5]

Climate psychology is more likely to explore the pathology in climate denial. Paul Hoggett describes as “the greatest mystery of our age” “our collective equanimity in the face of the unprecedented risk” of climate change.[6] Robert Gifford highlights the important role for psychologists (and I would add, Christian ministers) “if the many psychological barriers are to be overcome.” He warns that “denial remains a particularly troubling barrier … because behavior change cannot occur as long as the problem is not seen as a problem.”[7] This is not a neutral space; much research is “for the sake of channelling emotional energy to constructive responses to climate risks.”[8]

A Treaty perspective warns that psychology is a western system which splits people up into individual units and carries dangerous power to label spiritual and indigenous truth as abnormal. It is hard for me to see beyond the individualism of my culture and professional training. Ecclesiology helps me think collectively; church as body is closer to non-western ways of seeing the world. How do we journey into a warming world together, not just as a bunch of mini whirls of emotion bumping into each other? Maybe ‘whose’ I am is more important than who ‘I’ am and how ‘I’ feel.

It is also entirely possible that non-western people think and feel very differently than white folks about the natural world in general and climate change in particular. Sarah Jaquette Ray observes that Indigenous and Black people are more concerned about climate change but white people are more anxious about it, and warns that, “We can’t fight climate change with more racism. Climate anxiety must be directed toward addressing the ways that racism manifests as environmental trauma and vice versa.”[9] Climate psychologists shine light on equity, calling out the “double injustice, as the most marginalized, those who had the least to do with creating this mess—predominantly poor people of colour—are disproportionately harmed by a warming world.”[10]

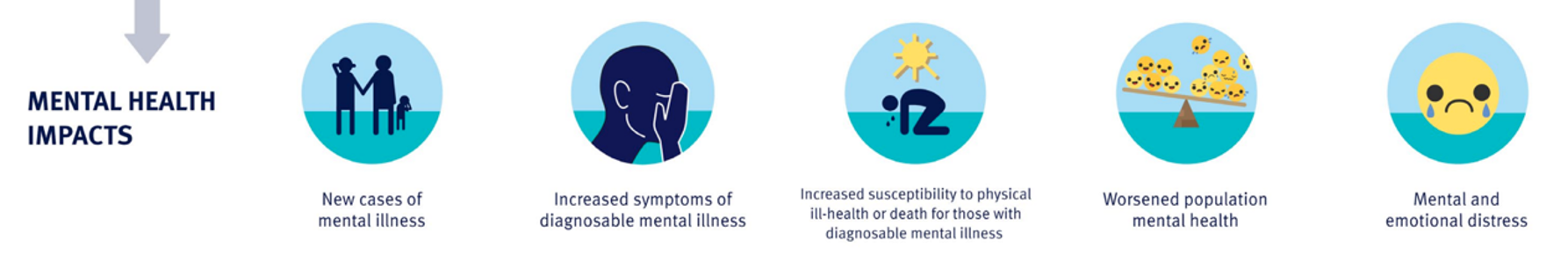

How climate change affects mental health is shaped by whether people are experiencing impacts indirectly or directly.[11] Direct impacts include increased risk of suicide when the weather is extremely hot, or increased family violence after a disaster. Indirect impacts include anxiety from hearing news of climate change. In the middle are a miriad of complexities leading to overall worsening mental health. I worry about ‘community breakdown’ and see the vital role for local churches in sustaining a healthy sense of caring for each other no matter what we face.

Is feeling bad about climate change a bad thing? To pathologise or not to pathologise? The powerful American Psychological Association decided not to define climate anxiety as a form of mental illness, moving away from an individualist medical model to call attention to “justice, equity, and mental health considerations.” “While resilience efforts are necessary to protect the physical and mental health of people and communities in the face of climate change, they fall short of addressing the problem at its root. Rapid transitions … require multilevel governance, policy instruments, institutional capacity, and investment.”[4] Christina Johannessen argues that “climate change stress should not be seen just as a problem to be solved or a condition to be medicated but rather an important encounter with our awareness of our impact on the world.”[5]

Climate psychology is more likely to explore the pathology in climate denial. Paul Hoggett describes as “the greatest mystery of our age” “our collective equanimity in the face of the unprecedented risk” of climate change.[6] Robert Gifford highlights the important role for psychologists (and I would add, Christian ministers) “if the many psychological barriers are to be overcome.” He warns that “denial remains a particularly troubling barrier … because behavior change cannot occur as long as the problem is not seen as a problem.”[7] This is not a neutral space; much research is “for the sake of channelling emotional energy to constructive responses to climate risks.”[8]

A Treaty perspective warns that psychology is a western system which splits people up into individual units and carries dangerous power to label spiritual and indigenous truth as abnormal. It is hard for me to see beyond the individualism of my culture and professional training. Ecclesiology helps me think collectively; church as body is closer to non-western ways of seeing the world. How do we journey into a warming world together, not just as a bunch of mini whirls of emotion bumping into each other? Maybe ‘whose’ I am is more important than who ‘I’ am and how ‘I’ feel.

It is also entirely possible that non-western people think and feel very differently than white folks about the natural world in general and climate change in particular. Sarah Jaquette Ray observes that Indigenous and Black people are more concerned about climate change but white people are more anxious about it, and warns that, “We can’t fight climate change with more racism. Climate anxiety must be directed toward addressing the ways that racism manifests as environmental trauma and vice versa.”[9] Climate psychologists shine light on equity, calling out the “double injustice, as the most marginalized, those who had the least to do with creating this mess—predominantly poor people of colour—are disproportionately harmed by a warming world.”[10]

How climate change affects mental health is shaped by whether people are experiencing impacts indirectly or directly.[11] Direct impacts include increased risk of suicide when the weather is extremely hot, or increased family violence after a disaster. Indirect impacts include anxiety from hearing news of climate change. In the middle are a miriad of complexities leading to overall worsening mental health. I worry about ‘community breakdown’ and see the vital role for local churches in sustaining a healthy sense of caring for each other no matter what we face.

Reports such as this emphasise the importance of ‘co-benefits’ for environmental, physical, social and mental health. It turns out that doing positive things for creation also helps us be well: “Individual and collective actions can also provide a greater sense of agency and control, increase feelings of meaning and empowerment, and provide social support.”[12] In the church we call this mission.

2: Self-Awareness

As a therapist I am drawn towards the connections between mind and body and the way we feel what we feel. But I am learning to first name where I stand and who stands with me, both from this generation and those gone before.

Belonging is obvious to me: I am found in Christ and Christ in me. First and foremost I honour God. Beyond that gets more complex, because my story is of settling and leaving, settling and leaving, during my life and for several generations. I have found a home in many places and communities, and am now in a time of re-settling. I feel envy for those with an enduring sense of place and belonging. Self-awareness of climate emotions enquires about which places we truly love, and asks of us a sustained capacity to care for the natural world, at least bits of it.

The people with me include my father, Ernest Crane, who found the courage of his convictions leading him to defy the machinery of war and willingly be imprisoned for his commitment to peace as an outworking of following Jesus. He was a teacher of geography, and a gardener, who taught me to see the land and to care for it. In my Presbyterian heritage I name Sister Annie Henry, who dedicated her life and heart to the Tūhoe people, based in Ruatāhuna, and is a model for me of capacity to cross between worlds while sustaining a passionate love for God and for all God’s children.

God planted a concern for the Earth into the centre of my call to ordination. I successfully ignored this for many years until joining A Rocha forged fresh passion for ecological mission. I engaged in conversations and reading that confronted me with the very serious and complex threats of global warming and I started to grapple with the implications, including for myself emotionally. I heard from the church a deafening silence on the subject, and knew that God was calling me to lead in this space. My own emotions about climate change (and all the other forms of environmental degradation) are deeply intertwined with my call to minister the Gospel of Christ. Others feel this integration in response to human trafficking or child poverty or a local community; it’s how God forms us as missional leaders to care in very specific ways.

For me, the primary challenge of climate change is the sheer vastness of it. The warnings of extinctions and sea-level rise and compounding catastrophes are cognitively enormously difficult to ‘get my head around’. As I have worked my way into exploring implications for the church and community sector I grapple with warnings of food shortgage and fires and conflict that far exceed anything I have experienced, or that we have yet seen in Aotearoa. So when I hear news of the current ‘cost of living crisis’ my response is, ‘we aint seen nothing yet!’ Here in Aotearoa we are relatively well insulated against the effects of global warming. It will still rain here, which is great, but probably too much at once, and not much out east.

The implications of climate science predictions impose themselves into my imagining. In Kaikoura I picture the whale watch centre becoming a memorial to the extinct whales. When my colleagues talk of a future of harmony and new earth consciousness I see only conflict and the fragility of the systems we take for granted. I live with a profound sadness. We had been given so much and used it so poorly. I wonder at the vast resources of human civilisation and technology; we could have overcome world hunger but instead we made cat videos.

The sadness I feel for the world hovers in the background of my daily life. I feel it as a heaviness in my bones. It can be hard to breathe freely or feel happy. It makes other things feel irrelevant or trivial. I can feel tired. I am hugely blessed, with an excellent marriage, a healthy body, money in the bank, food in the pantry and a beautiful home. I have mana in my community and awesome friends. But when I do experience rejection or failure or fatigue, my climate sadness makes me more vulnerable. I learn to be kind to myself. It is not eased by prayer. It is not a lack of faith. It just is. I suspect it’s how God feels too.

The odd thing about this sorrow is that I do not expect to recover from it. When my father died I grieved for him and that healed into gratitude for his life. Ecological grief has no end point. I fully expect it to get stronger through the years as losses increase. The only solution I see is to be so hollowed out and utterly surrendered to God that peace and joy blossom in the presence of sadness – not of my own making but only because Christ died and rose again.

I am not surprised or shocked by disasters. I expect them. I rarely feel anxious or angry. I realise that City Councils want more rates income so they approve new buildings on land prone to floods and sea rise. It’s wrong, and we need to advocate for climate resilient decision making, but I don’t often feel angry about it. Mind you, it’s not my home at risk of being washed out. I feel empathy for those traumatised by disaster, but I lean towards long-term solutions: good risk assessment and planning, people trained in disaster chaplaincy and pastoral care. How do we form in ourselves as community leaders the emotional capacity to deal with high levels of demand and insecurity?

A few years ago I was focused on personal and community change towards sustainable living. I still care about reducing waste and fuel consumption, but my sadness tells me that I have mostly given up on avoiding climate crisis. We had our window to change and we have not changed. We continue globally to burn more fossil fuels, despite overwhelming evidence of the trajectory we are on. So I no longer feel guilty about buying my kids air tickets to come to a family weekend. I’m grateful our family are all in Aotearoa. I am grateful for the overseas travel I have done and I don’t plan to leave the country again. Guilt is an appropriate emotion, especially for us resource-greedy white middle-class. By all means grapple with personal responsibility. God forgives our sin but I suspect that the Earth is losing her capacity to forgive our sins against creation. But I don’t live with guilt. I know that I do what God has given me to do.

Climate psychology includes an invitation to ‘look on the bright side’ as well as facing the ‘doom and gloom’. The positive emotions I feel in response to climate change include a real sense of excitement about the emerging mission movement of creation care, which I see as a work of the Holy Spirit in our time. I love the teams I am part of, and fabulous people doing inspiring things.[13] I must also confess my own need for status and recognition. I am motivated and inspired to lead into new territory, and this is fulfilling and enjoyable, but there’s a note of caution in my head warning me not to use climate crisis as a path to personal fame and the applause of others.

I am grateful that underlying inequities and consequences of human systems (including colonisation) are being exposed. The Bible word for ‘revealing’ is ‘apocalypse’. I think and feel in apocalyptic terms. There’s more going on than can be measured by scientists. If God is bringing judgement on human sin writ large, then I am OK with that. I trust God’s judgement, as terrifying as that might be.

Belonging is obvious to me: I am found in Christ and Christ in me. First and foremost I honour God. Beyond that gets more complex, because my story is of settling and leaving, settling and leaving, during my life and for several generations. I have found a home in many places and communities, and am now in a time of re-settling. I feel envy for those with an enduring sense of place and belonging. Self-awareness of climate emotions enquires about which places we truly love, and asks of us a sustained capacity to care for the natural world, at least bits of it.

The people with me include my father, Ernest Crane, who found the courage of his convictions leading him to defy the machinery of war and willingly be imprisoned for his commitment to peace as an outworking of following Jesus. He was a teacher of geography, and a gardener, who taught me to see the land and to care for it. In my Presbyterian heritage I name Sister Annie Henry, who dedicated her life and heart to the Tūhoe people, based in Ruatāhuna, and is a model for me of capacity to cross between worlds while sustaining a passionate love for God and for all God’s children.

God planted a concern for the Earth into the centre of my call to ordination. I successfully ignored this for many years until joining A Rocha forged fresh passion for ecological mission. I engaged in conversations and reading that confronted me with the very serious and complex threats of global warming and I started to grapple with the implications, including for myself emotionally. I heard from the church a deafening silence on the subject, and knew that God was calling me to lead in this space. My own emotions about climate change (and all the other forms of environmental degradation) are deeply intertwined with my call to minister the Gospel of Christ. Others feel this integration in response to human trafficking or child poverty or a local community; it’s how God forms us as missional leaders to care in very specific ways.

For me, the primary challenge of climate change is the sheer vastness of it. The warnings of extinctions and sea-level rise and compounding catastrophes are cognitively enormously difficult to ‘get my head around’. As I have worked my way into exploring implications for the church and community sector I grapple with warnings of food shortgage and fires and conflict that far exceed anything I have experienced, or that we have yet seen in Aotearoa. So when I hear news of the current ‘cost of living crisis’ my response is, ‘we aint seen nothing yet!’ Here in Aotearoa we are relatively well insulated against the effects of global warming. It will still rain here, which is great, but probably too much at once, and not much out east.

The implications of climate science predictions impose themselves into my imagining. In Kaikoura I picture the whale watch centre becoming a memorial to the extinct whales. When my colleagues talk of a future of harmony and new earth consciousness I see only conflict and the fragility of the systems we take for granted. I live with a profound sadness. We had been given so much and used it so poorly. I wonder at the vast resources of human civilisation and technology; we could have overcome world hunger but instead we made cat videos.

The sadness I feel for the world hovers in the background of my daily life. I feel it as a heaviness in my bones. It can be hard to breathe freely or feel happy. It makes other things feel irrelevant or trivial. I can feel tired. I am hugely blessed, with an excellent marriage, a healthy body, money in the bank, food in the pantry and a beautiful home. I have mana in my community and awesome friends. But when I do experience rejection or failure or fatigue, my climate sadness makes me more vulnerable. I learn to be kind to myself. It is not eased by prayer. It is not a lack of faith. It just is. I suspect it’s how God feels too.

The odd thing about this sorrow is that I do not expect to recover from it. When my father died I grieved for him and that healed into gratitude for his life. Ecological grief has no end point. I fully expect it to get stronger through the years as losses increase. The only solution I see is to be so hollowed out and utterly surrendered to God that peace and joy blossom in the presence of sadness – not of my own making but only because Christ died and rose again.

I am not surprised or shocked by disasters. I expect them. I rarely feel anxious or angry. I realise that City Councils want more rates income so they approve new buildings on land prone to floods and sea rise. It’s wrong, and we need to advocate for climate resilient decision making, but I don’t often feel angry about it. Mind you, it’s not my home at risk of being washed out. I feel empathy for those traumatised by disaster, but I lean towards long-term solutions: good risk assessment and planning, people trained in disaster chaplaincy and pastoral care. How do we form in ourselves as community leaders the emotional capacity to deal with high levels of demand and insecurity?

A few years ago I was focused on personal and community change towards sustainable living. I still care about reducing waste and fuel consumption, but my sadness tells me that I have mostly given up on avoiding climate crisis. We had our window to change and we have not changed. We continue globally to burn more fossil fuels, despite overwhelming evidence of the trajectory we are on. So I no longer feel guilty about buying my kids air tickets to come to a family weekend. I’m grateful our family are all in Aotearoa. I am grateful for the overseas travel I have done and I don’t plan to leave the country again. Guilt is an appropriate emotion, especially for us resource-greedy white middle-class. By all means grapple with personal responsibility. God forgives our sin but I suspect that the Earth is losing her capacity to forgive our sins against creation. But I don’t live with guilt. I know that I do what God has given me to do.

Climate psychology includes an invitation to ‘look on the bright side’ as well as facing the ‘doom and gloom’. The positive emotions I feel in response to climate change include a real sense of excitement about the emerging mission movement of creation care, which I see as a work of the Holy Spirit in our time. I love the teams I am part of, and fabulous people doing inspiring things.[13] I must also confess my own need for status and recognition. I am motivated and inspired to lead into new territory, and this is fulfilling and enjoyable, but there’s a note of caution in my head warning me not to use climate crisis as a path to personal fame and the applause of others.

I am grateful that underlying inequities and consequences of human systems (including colonisation) are being exposed. The Bible word for ‘revealing’ is ‘apocalypse’. I think and feel in apocalyptic terms. There’s more going on than can be measured by scientists. If God is bringing judgement on human sin writ large, then I am OK with that. I trust God’s judgement, as terrifying as that might be.

3: Climate Aware Pastoral Care

In this section I explore five pathways of pastoral practice that enable carers to be safe and effective partners for people experiencing distress around climate change.

a) Ngā here: Climate aware pastoral care makes connections

First, we make a connection. You and me, sharing a space together, here and now. The quality of a pastoral conversation is the quality of the connection between us. In Te Reo, care is manaaki, intimately related to manaakitanga, hospitality. Whether I host a client in my home and make them a cup of tea, or we meet online, or in a cafe or their own home, I am fully present to them. I create space by my own inner stillness, in which this person is safe to be themselves. I’ll say enough about myself to enable genuine connection. I’m not just a mirror or a technician. This is a real relationship.

The next layer is connecting with God. Sometimes conscious, mosly outside of our awareness, Jesus is a conversation partner. Thomas Oden describes pastoral care as “a co-working ministry day after day with Christ’s own ministry, supported and energized by the Holy Spirit ... it calls us always to look for footprints of Christ’s presence before us, all along the way.”[14]

Third, we honour the connections people have with where they have come from. We Pākehā aren’t great at this, assuming (bizarrely) that this moment in time is disconnected from all that has gone before. Bicultural practice trains us to flesh out links with whakapapa, links to family and land and foundations of belonging. I find that people are often dismissing or critical of their family backgrounds, but there is healing power in standing in a particular place with particular people, over generations.

Fourth, I am a strong advocate of helping people connect with their own body. I ask people to pause, relax, breathe in and out, and notice how and where they feel what they feel. Again and again this creates space for Wairua Tapu to get a word in, to speak peace and truth in tangible ways. It is what I love most about the work I do.

Fifth, this work brings creation into the conversation. Those who are stressed about climate change have a conflicted connection with the natural world. On one hand they have a deep (I would say God-given) love for nature. On the other hand, fears and sadness about threats make nature unsafe, even triggering of trauma. It’s a horrible catch-22 as climate crisis blocks access to the very thing which enables healing of climate stress. Climate aware care gently encourages ways to restore love and safety, which enables people to re-experience God through creation.

And lastly, climate aware practice nurtures wider connections. A focus on climate emotions risks viewing people as individual sets of inner experience. We must see through the limitations of a western world-view. The fundamental nature of climate change is that we are in this together, every human on the planet. Our connectedness with each other matters far more than our individual uniqueness. Pastoral care is always on the look-out for opportunities to connect this person with others. Church can (on a good day) be good at this.

b) Awhihia te mamae: Climate aware pastoral care holds uncomfortable space

Byron Smith describes the discomfort of climate change:

“We are guilty of unleashing an unparalleled threat that we feel helpless to prevent. This constellation of factors is historically novel and so is the quality of the associated experience of fear. While the threats fall somewhere on a scale that ranges from disastrous to truly catastrophic, fears are often muted, confused, riddled with guilt and impotence, and ineffective in generating anything like the scale of concerted action required to address the threat.”[15]

Effective pastoral care is a safe holding space in the presence of this strange mix of emotions. Britt Wray describes the need for “a container for our overwhelming emotions. The idea with containment is that any experience, even difficult ones, can be food for thought, and therefore growth and development, if it is processed in a way that helps a person understand their own feelings.”[16] This is a process of being held, which enables people to stay present and engaged, both with the difficult realities they see in the world and with the difficult emotions they feel in response.

But what does this require of us? How do we embody a calm that enables the stress of others to fade? How do I both communicate genuinely care and sustain in myself the ability to genuinely care? The word ‘awhi’ means at its most literal level a hug; two people putting their arms around each other. Physical hugs are not always appropriate in counselling or pastoral care, but emotional and spiritual ‘awhi’ is the very essence of what we offer. In the church we are excellent at this when someone has lost a loved one or has a cancer diagnosis. We are not so good (yet!) at holding one another through grief and pain related to climate change.

c) He aha atu? Climate aware pastoral care asks ‘What else?’

Few people begin a pastoral conversation by talking about climate change. University chaplains report that a deep anxiety about the world “runs constantly on other levels during pastoral care conversations” with students. It comes out “through short statements or quick words and questions.” The research concludes that “we are dealing with invisible connections and lines, which somehow inseparably cling to the students’ state of mind as “foil”— penetrating the things that go on in the lives of the students.”[17] I find this research fascinating, revealing the subtle complex ways in which climate change affects people. Most people, most of the time, are good at pushing their underlying climate emotions out of awareness, only emerging in fragments of communication, and only able to be brought out into full awareness when another person is fully listening and encouraging.

This requires of pastoral carers that we ourselves have done this work, or we will simply fail to notice climate distress. It also requires that we keep attending and asking beyond the superficial. It demands curiosity about complexity, especially emotional complexity, and choosing not to settle for easy answers in order to make someone feel better. Britt Wray suggests that “to fully process these complex feelings, we must move away from the positivist psychological framing that sees some feelings as bad and others as good. Despair and fear are not inherently bad. Hope and optimism are not inherently good. ... There is meaning in every emotion.”[18]

Specifically this looks like listening calmly and attentively, and then wondering “what else are you feeling?” It comes from an attitude of gentle curiosity, undemanding, inviting more and more aspects of a person’s inner experience to enter the conversation, and so be open to the Spirit’s touch.

d) Pātai uaua: Climate aware pastoral care asks hard questions of God

Climate theology is not for the faint hearted. Climate change threatens the stability of our world; for much of Christian history the stability of creation is evidence for the steadfast loving faithfulness of God. It confronts us with the questions of theodicy: why bad things happen, even to good people, and whether God can be both good and powerful in the face of evidence of terrible wrong.

There are various ways to respond theologically to climate change. Some ‘eco-theologies’ call Christians to reject traditional ideas about God and move into a new global ‘Earth consciousness’.[19] Other forms of theology emphasise the imminent end of the world and God’s sovereign power to remake creation entirely. Some emphasise stewardship, kaitiakitanga, and sustainable lifestyles. Justice theology calls attention to God’s heart for the poor and invites theologies of protest and resistance. Indigenous theologies invite deep respect for the land and sea and all living things, and deconstruct colonial forms of thinking about God.

The ‘ask’ for pastoral care is to be genuinely curious about how this person, here and now, is connecting their ideas about God with their feelings about the world. My theological reflections are a resource which I can offer during a pastoral conversation, but only lightly sprinkled, like salt, not dumped on another person. Pastoral care is the art of asking good questions. One of the best is to ask what questions you have, to help you explore your own answers, trusting that God is speaking to you. I facilitate that as the care-giver.

The specific challenge of climate change is that our questions for God do not have easy answers: Why? How could you let this happen if you are Lord of all? People have always asked painful questions of God, whenever painful things happen. The Bible is full of these difficult places, the gaps between faith and experience, trust and betrayal: where are you? how long? why have you abandoned me? We rush too quickly to the nice bits, the warm-fuzzy promises and reassurances. Ask hard questions. God can handle it.

e) Kia kaha, kia maia: Climate aware pastoral care empowers action

James warned that faith without works is dead (James 2:17). In response to environmental damage and climate threats, awareness without action reenforces the deadness of apathy and powerlessness. Good pastoral listening releases energy and clarity for personal and collective mission. “Rather than bury our heads in the sand and suppress our discomfort, we can harness and transform the distress we feel into meaningful actions and forms of connection.”[20] Britt Wray’s call is to “be wakeful, internally strengthened, and externally motivated.”[21] “If we don’t recognize our eco-distress, and learn to purposefully and justly transform it, we’ll miss the opportunity we have to use all this restless energy for a deeper purpose: to bring forth the future we owe each other by promoting solutions that have co-benefits for all people and the planet.”[22] Byron Smith argues that “participating in movements for change does lend a sense of agency.”[23]

However, this comes with a warning: Caroline Hickman warns of the danger in seeking a shortcut, “a too-quick move from pain to action” as focusing only on climate action can leave people less resilient and capable of facing the ecological crisis.[24] The fact is, many of our goals for climate action will likely result in failure, and so to burn-out and fatigue.

Connecting with other people who ‘get it’ is a vital component to ‘living well’ in climate crisis. It is precisely for this reason that Christians in climate-denying churches feel so alienated. Ever since we formed the Eco Church movement in Aotearoa, people have been telling me how lonely they are in their church, and how profoundly they feel the disconnect between their professional work and personal convictions and where their church is at. This truly grieves me, for it crushes the work of the Holy Spirit in forming the church as authentic safe space to belong.

For the church, ‘kia kaha kia maia’ is a call to missional courage. I passionately advocate for collective faithful action on behalf of communities of faith at all levels to respond to the massive threats facing God’s creation. And we are seeing how practical opportunities to engage in supportive effective shared action has significant benefits for people’s mental health and sense of hope for the future. This is a key form of evangelism and outreach, as well as a call to integrity as we seek to be Jesus people in our time.

a) Ngā here: Climate aware pastoral care makes connections

First, we make a connection. You and me, sharing a space together, here and now. The quality of a pastoral conversation is the quality of the connection between us. In Te Reo, care is manaaki, intimately related to manaakitanga, hospitality. Whether I host a client in my home and make them a cup of tea, or we meet online, or in a cafe or their own home, I am fully present to them. I create space by my own inner stillness, in which this person is safe to be themselves. I’ll say enough about myself to enable genuine connection. I’m not just a mirror or a technician. This is a real relationship.

The next layer is connecting with God. Sometimes conscious, mosly outside of our awareness, Jesus is a conversation partner. Thomas Oden describes pastoral care as “a co-working ministry day after day with Christ’s own ministry, supported and energized by the Holy Spirit ... it calls us always to look for footprints of Christ’s presence before us, all along the way.”[14]

Third, we honour the connections people have with where they have come from. We Pākehā aren’t great at this, assuming (bizarrely) that this moment in time is disconnected from all that has gone before. Bicultural practice trains us to flesh out links with whakapapa, links to family and land and foundations of belonging. I find that people are often dismissing or critical of their family backgrounds, but there is healing power in standing in a particular place with particular people, over generations.

Fourth, I am a strong advocate of helping people connect with their own body. I ask people to pause, relax, breathe in and out, and notice how and where they feel what they feel. Again and again this creates space for Wairua Tapu to get a word in, to speak peace and truth in tangible ways. It is what I love most about the work I do.

Fifth, this work brings creation into the conversation. Those who are stressed about climate change have a conflicted connection with the natural world. On one hand they have a deep (I would say God-given) love for nature. On the other hand, fears and sadness about threats make nature unsafe, even triggering of trauma. It’s a horrible catch-22 as climate crisis blocks access to the very thing which enables healing of climate stress. Climate aware care gently encourages ways to restore love and safety, which enables people to re-experience God through creation.

And lastly, climate aware practice nurtures wider connections. A focus on climate emotions risks viewing people as individual sets of inner experience. We must see through the limitations of a western world-view. The fundamental nature of climate change is that we are in this together, every human on the planet. Our connectedness with each other matters far more than our individual uniqueness. Pastoral care is always on the look-out for opportunities to connect this person with others. Church can (on a good day) be good at this.

b) Awhihia te mamae: Climate aware pastoral care holds uncomfortable space

Byron Smith describes the discomfort of climate change:

“We are guilty of unleashing an unparalleled threat that we feel helpless to prevent. This constellation of factors is historically novel and so is the quality of the associated experience of fear. While the threats fall somewhere on a scale that ranges from disastrous to truly catastrophic, fears are often muted, confused, riddled with guilt and impotence, and ineffective in generating anything like the scale of concerted action required to address the threat.”[15]

Effective pastoral care is a safe holding space in the presence of this strange mix of emotions. Britt Wray describes the need for “a container for our overwhelming emotions. The idea with containment is that any experience, even difficult ones, can be food for thought, and therefore growth and development, if it is processed in a way that helps a person understand their own feelings.”[16] This is a process of being held, which enables people to stay present and engaged, both with the difficult realities they see in the world and with the difficult emotions they feel in response.

But what does this require of us? How do we embody a calm that enables the stress of others to fade? How do I both communicate genuinely care and sustain in myself the ability to genuinely care? The word ‘awhi’ means at its most literal level a hug; two people putting their arms around each other. Physical hugs are not always appropriate in counselling or pastoral care, but emotional and spiritual ‘awhi’ is the very essence of what we offer. In the church we are excellent at this when someone has lost a loved one or has a cancer diagnosis. We are not so good (yet!) at holding one another through grief and pain related to climate change.

c) He aha atu? Climate aware pastoral care asks ‘What else?’

Few people begin a pastoral conversation by talking about climate change. University chaplains report that a deep anxiety about the world “runs constantly on other levels during pastoral care conversations” with students. It comes out “through short statements or quick words and questions.” The research concludes that “we are dealing with invisible connections and lines, which somehow inseparably cling to the students’ state of mind as “foil”— penetrating the things that go on in the lives of the students.”[17] I find this research fascinating, revealing the subtle complex ways in which climate change affects people. Most people, most of the time, are good at pushing their underlying climate emotions out of awareness, only emerging in fragments of communication, and only able to be brought out into full awareness when another person is fully listening and encouraging.

This requires of pastoral carers that we ourselves have done this work, or we will simply fail to notice climate distress. It also requires that we keep attending and asking beyond the superficial. It demands curiosity about complexity, especially emotional complexity, and choosing not to settle for easy answers in order to make someone feel better. Britt Wray suggests that “to fully process these complex feelings, we must move away from the positivist psychological framing that sees some feelings as bad and others as good. Despair and fear are not inherently bad. Hope and optimism are not inherently good. ... There is meaning in every emotion.”[18]

Specifically this looks like listening calmly and attentively, and then wondering “what else are you feeling?” It comes from an attitude of gentle curiosity, undemanding, inviting more and more aspects of a person’s inner experience to enter the conversation, and so be open to the Spirit’s touch.

d) Pātai uaua: Climate aware pastoral care asks hard questions of God

Climate theology is not for the faint hearted. Climate change threatens the stability of our world; for much of Christian history the stability of creation is evidence for the steadfast loving faithfulness of God. It confronts us with the questions of theodicy: why bad things happen, even to good people, and whether God can be both good and powerful in the face of evidence of terrible wrong.

There are various ways to respond theologically to climate change. Some ‘eco-theologies’ call Christians to reject traditional ideas about God and move into a new global ‘Earth consciousness’.[19] Other forms of theology emphasise the imminent end of the world and God’s sovereign power to remake creation entirely. Some emphasise stewardship, kaitiakitanga, and sustainable lifestyles. Justice theology calls attention to God’s heart for the poor and invites theologies of protest and resistance. Indigenous theologies invite deep respect for the land and sea and all living things, and deconstruct colonial forms of thinking about God.

The ‘ask’ for pastoral care is to be genuinely curious about how this person, here and now, is connecting their ideas about God with their feelings about the world. My theological reflections are a resource which I can offer during a pastoral conversation, but only lightly sprinkled, like salt, not dumped on another person. Pastoral care is the art of asking good questions. One of the best is to ask what questions you have, to help you explore your own answers, trusting that God is speaking to you. I facilitate that as the care-giver.

The specific challenge of climate change is that our questions for God do not have easy answers: Why? How could you let this happen if you are Lord of all? People have always asked painful questions of God, whenever painful things happen. The Bible is full of these difficult places, the gaps between faith and experience, trust and betrayal: where are you? how long? why have you abandoned me? We rush too quickly to the nice bits, the warm-fuzzy promises and reassurances. Ask hard questions. God can handle it.

e) Kia kaha, kia maia: Climate aware pastoral care empowers action

James warned that faith without works is dead (James 2:17). In response to environmental damage and climate threats, awareness without action reenforces the deadness of apathy and powerlessness. Good pastoral listening releases energy and clarity for personal and collective mission. “Rather than bury our heads in the sand and suppress our discomfort, we can harness and transform the distress we feel into meaningful actions and forms of connection.”[20] Britt Wray’s call is to “be wakeful, internally strengthened, and externally motivated.”[21] “If we don’t recognize our eco-distress, and learn to purposefully and justly transform it, we’ll miss the opportunity we have to use all this restless energy for a deeper purpose: to bring forth the future we owe each other by promoting solutions that have co-benefits for all people and the planet.”[22] Byron Smith argues that “participating in movements for change does lend a sense of agency.”[23]

However, this comes with a warning: Caroline Hickman warns of the danger in seeking a shortcut, “a too-quick move from pain to action” as focusing only on climate action can leave people less resilient and capable of facing the ecological crisis.[24] The fact is, many of our goals for climate action will likely result in failure, and so to burn-out and fatigue.

Connecting with other people who ‘get it’ is a vital component to ‘living well’ in climate crisis. It is precisely for this reason that Christians in climate-denying churches feel so alienated. Ever since we formed the Eco Church movement in Aotearoa, people have been telling me how lonely they are in their church, and how profoundly they feel the disconnect between their professional work and personal convictions and where their church is at. This truly grieves me, for it crushes the work of the Holy Spirit in forming the church as authentic safe space to belong.

For the church, ‘kia kaha kia maia’ is a call to missional courage. I passionately advocate for collective faithful action on behalf of communities of faith at all levels to respond to the massive threats facing God’s creation. And we are seeing how practical opportunities to engage in supportive effective shared action has significant benefits for people’s mental health and sense of hope for the future. This is a key form of evangelism and outreach, as well as a call to integrity as we seek to be Jesus people in our time.

Notes:

[1] By the ‘Treaty’ I mean Te Tiriti o Waitangi, the founding document of Aotearoa New Zealand, which is a framework for justice and cultural respect, and relevant in all forms of professional practice.

[2] Pihkala P. (2022) ‘Toward a Taxonomy of Climate Emotions.’ Frontiers in Climate. 3:738154. doi: 10.3389, p1.

[3] ibid, p2.

[4] Clayton, S., C. M. Manning, M. Speiser & A. N. Hill (2021). ‘Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Inequities, Responses.’ American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica, p7.

[5] Johannessen, C. T. (2022) ‘Belonging to the World through Body, Trust, and Trinity: Climate Change and Pastoral Care with University Students.’ Religions 13, no. 6: 527, https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060527, p2

[6] Hoggett, P (ed.) (2019) Climate Psychology: On Indifference to Disaster. Palgrave, Springer, p16.

[7] Gifford, R (2011) ‘The Dragons of Inaction: Psychological Barriers That Limit Climate Change.’ American Psychologist, May 2011, DOI: 10.1037/a0023566, p298.

[8] Pihkala (2022), p3.

[9] Sarah J. R., ‘Climate Anxiety Is an Overwhelmingly White Phenomenon.’ Scientific American, 21 March 2021.

[10] Wray, B. (2022) Generation Dread: Finding purpose in an age of climate crisis. Knopf Canada.

[11] Lawrance, E. et.al. (2012) ‘The impact of climate change on mental health and emotional wellbeing: current evidence and implications for policy and practice.’ Grantham Institute Briefing paper 36, Institute of Global Health Innovation. Diagram is “Figure 6: Examples of the continuum of impacts that climate change has on mental health outcomes,” p.10.

[12] Lawrance (2012), p.15.

[13] I got to document 30 such stories in Awhi Mai Awhi Atu: Women in Creation Care (2022), Silvia Purdie (ed.) Philip Garside Books.

[14] Oden, T. C. (1983) Pastoral Theology: Essentials of Ministry, Harper & Row, p193.

[15] Smith, B. (2017) ‘Waking up to a Warming World: Prospects for Christian Ethical Deliberation amidst Climate Fears.’ PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh, p43.

[16] Wray (2022), p73.

[17] Johannessen, p5.

[18] Wray, B. (2022), p110.

[19] As I read scripture I am confronted over and over by humanity’s need to create idols, and to worship things other than the living God. Climate crisis is fueled by our passion for the idols of money, pleasure and status. I sincerely believe that the solution is not to replace these with ‘green’ idols. All idolatory is a form of enslavement, and Christ came to set us free.

[20] Wray (2022), p8-9.

[21] ibid, p10.

[22] ibid, p33.

[23] Smith (2017), p33.

[24] Wray (2022), p110.

[1] By the ‘Treaty’ I mean Te Tiriti o Waitangi, the founding document of Aotearoa New Zealand, which is a framework for justice and cultural respect, and relevant in all forms of professional practice.

[2] Pihkala P. (2022) ‘Toward a Taxonomy of Climate Emotions.’ Frontiers in Climate. 3:738154. doi: 10.3389, p1.

[3] ibid, p2.

[4] Clayton, S., C. M. Manning, M. Speiser & A. N. Hill (2021). ‘Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Inequities, Responses.’ American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica, p7.

[5] Johannessen, C. T. (2022) ‘Belonging to the World through Body, Trust, and Trinity: Climate Change and Pastoral Care with University Students.’ Religions 13, no. 6: 527, https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060527, p2

[6] Hoggett, P (ed.) (2019) Climate Psychology: On Indifference to Disaster. Palgrave, Springer, p16.

[7] Gifford, R (2011) ‘The Dragons of Inaction: Psychological Barriers That Limit Climate Change.’ American Psychologist, May 2011, DOI: 10.1037/a0023566, p298.

[8] Pihkala (2022), p3.

[9] Sarah J. R., ‘Climate Anxiety Is an Overwhelmingly White Phenomenon.’ Scientific American, 21 March 2021.

[10] Wray, B. (2022) Generation Dread: Finding purpose in an age of climate crisis. Knopf Canada.

[11] Lawrance, E. et.al. (2012) ‘The impact of climate change on mental health and emotional wellbeing: current evidence and implications for policy and practice.’ Grantham Institute Briefing paper 36, Institute of Global Health Innovation. Diagram is “Figure 6: Examples of the continuum of impacts that climate change has on mental health outcomes,” p.10.

[12] Lawrance (2012), p.15.

[13] I got to document 30 such stories in Awhi Mai Awhi Atu: Women in Creation Care (2022), Silvia Purdie (ed.) Philip Garside Books.

[14] Oden, T. C. (1983) Pastoral Theology: Essentials of Ministry, Harper & Row, p193.

[15] Smith, B. (2017) ‘Waking up to a Warming World: Prospects for Christian Ethical Deliberation amidst Climate Fears.’ PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh, p43.

[16] Wray (2022), p73.

[17] Johannessen, p5.

[18] Wray, B. (2022), p110.

[19] As I read scripture I am confronted over and over by humanity’s need to create idols, and to worship things other than the living God. Climate crisis is fueled by our passion for the idols of money, pleasure and status. I sincerely believe that the solution is not to replace these with ‘green’ idols. All idolatory is a form of enslavement, and Christ came to set us free.

[20] Wray (2022), p8-9.

[21] ibid, p10.

[22] ibid, p33.

[23] Smith (2017), p33.

[24] Wray (2022), p110.